Electric vehicles don't often come with the large front grilles their gas-powered cousins do—don't batteries need cooling, too?

Gasoline and diesel engines generate so much heat that if they’re not properly cooled, they can self-destruct in a matter of minutes. Electric vehicles (EVs) obviously don’t have that engine issue, but their batteries need to be cooled to help preserve their performance and lifespan. Computer Heatsink

Conventional vehicles pull air in through the front grille, but many EVs don’t even have a grille, and if they do, it’s mainly for looks instead of function. It may seem to you like it’d make more sense to keep the grille and use it for battery cooling, but it generally doesn’t work that way.

Instead, there are different methods for maintaining ideal battery temperature, known as thermal management. Even if air is used, EVs are designed with better ways to get air directly where it needs to be, for the battery and for any other components that require airflow. A front grille usually isn’t the most efficient method. The battery is naturally going to generate heat due to the current flow, and especially when the battery is being fast-charged. Air cooling is simple and relatively inexpensive, but liquid cooling, while more complex, does a better job.

An EV’s traction battery – the big one that powers the electric motors to turn the wheels – generally prefers to be somewhere between about 15 to 25 degrees Celsius.

At lower ambient temperatures, the battery won’t provide as much power, and the vehicle’s range can drop as much as 20 per cent when temperatures outside are below freezing. If the battery gets too hot, it will initially lose some of its power. If its internal temperature continues to rise, it can potentially degrade, suffer partial damage, or experience complete failure, including catching fire.

A liquid battery-cooling system works somewhat the same way as that of an internal-combustion engine. The coolant fluid is pumped through passages in the battery – usually inside a plate that cools the battery overall, or around the cells themselves.

As with a gasoline engine’s system, the fluid gets hot as it cools the battery, and is cooled in a heat exchanger – basically a small radiator – and then recirculated in a closed loop. That loop may include cooling other electronic components. The waste heat may also be used to help warm the cabin in winter.

While EVs have fewer maintenance requirements than gasoline vehicles, primarily in that they don’t need oil changes, they do need their coolant changed on a regular basis. If it isn’t, then as with a conventional radiator, the coolant can eventually break down, or the passages may get plugged with scale, reducing the system’s effectiveness. If you own an EV, check your owner’s manual for the maintenance schedule.

In addition to thermal management during driving, the liquid system also protects the battery during charging, especially when fast-charging on a DC charger. All charging creates heat, but the extra load of fast-charging can make a lot of it – including in the charger itself, which circulates its own coolant through its charging cable to regulate its temperature. The vehicle monitors its battery’s temperature during charging. If the cooling system isn’t doing enough, the vehicle will reduce its charging rate to bring down the temperature, especially if it’s a hot day. The battery will take longer to charge, but it’ll be better protected.

Air cooling can be achieved by simply letting air circulate around the battery cells, which is least effective; or by using a fan to increase the airflow. Some systems can also use the vehicle’s air conditioning unit to chill the air before it goes to the battery. Air cooling overall is simpler than liquid cooling, and the system weighs and costs less, but it isn’t as good. Not many vehicles use it, but one that does is the Nissan Leaf — although the upcoming Nissan Ariya EV is expected to use liquid cooling.

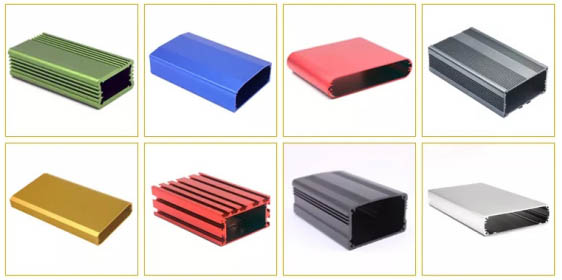

There are other methods of battery cooling, but they’re not really great for electric vehicles. Fins can be used to dissipate heat, as they are on some electronic components, but they add a lot of weight. There’s also phase change material, which changes from a solid to liquid as it absorbs heat. But it doesn’t then effectively transfer that heat away, and so it’s too inefficient for EV battery use.

Even a liquid-cooled EV uses some air for cooling various components, so why not bring that air in through a conventional-style grille? It’s all about effectiveness. Most EVs have a flat battery in the floor, to maximize cabin space and to lower the vehicle’s centre of gravity, and most of the components sit low in the vehicle as well. Instead of routing air down through the grille, most automakers use designs that incorporate the air intakes lower down and closer to the bumper, so the air comes in closer to what it’s intended to cool. Meanwhile, blocking off the grille area improves aerodynamics, which in turn can help improve range.

When it comes to EV styling, it isn’t just about making sure it doesn’t look like a gasoline car, but doing what’s needed because it also doesn’t work like a gasoline car.

· Professional writer for more than 35 years, appearing in some of the top publications in Canada and the U.S.

· Specialties include new-vehicle reviews, old cars and automotive history, automotive news, and “How It Works” columns that explain vehicle features and technology

· Member of the Automobile Journalists Association of Canada (AJAC) since 2003; voting member for AJAC Canadian Car of the Year Awards; juror on the Women’s World Car of the Year Awards

Jil McIntosh graduated from East York Collegiate in Toronto, and then continued her education at the School of Hard Knocks. Her early jobs including driving a taxi in Toronto; and warranty administration in a new-vehicle dealership, where she also held information classes for customers, explaining the inner mechanical workings of vehicles and their features.

Jil McIntosh is a freelance writer who has been writing for Driving.ca since 2016, but she’s been a professional writer starting when most cars still had carburetors. At the age of eleven, she had a story published in the defunct Toronto Telegram newspaper, for which she was paid $25; given the short length of the story and the dollar’s buying power at the time, that might have been the relatively best-paid piece she’s ever written.

An old-car enthusiast who owns a 1947 Cadillac and 1949 Studebaker truck, she began her writing career crafting stories for antique-car and hot-rod car club magazines. When the Ontario-based newspaper Old Autos started up in 1987, dedicated to the antique-car hobby, she became a columnist starting with its second issue; the newspaper is still around and she still writes for it. Not long after the Toronto Star launched its Wheels section in 1986 – the first Canadian newspaper to include an auto section – she became one of its regular writers. She started out writing feature stories, and then added “new-vehicle reviewer” to her resume in 1999. She stayed with Wheels, in print and later digital as well, until the publication made a cost-cutting decision to shed its freelance writers. She joined Driving.ca the very next day.

In addition to Driving.ca, she writes for industry-focused publications, including Automotive News Canada and Autosphere. Over the years, her automotive work also appeared in such publications as Cars & Parts, Street Rodder, Canadian Hot Rods, AutoTrader, Sharp, Taxi News, Maclean’s, The Chicago Tribune, Forbes Wheels, Canadian Driver, Sympatico Autos, and Reader’s Digest. Her non-automotive work, covering such topics as travel, food and drink, rural living, fountain pen collecting, and celebrity interviews, has appeared in publications including Harrowsmith, Where New Orleans, Pen World, The Book for Men, Rural Delivery, and Gambit.

2016 AJAC Journalist of the Year; Car Care Canada / CAA Safety Journalism award winner in 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2013, runner-up in 2021; Pirelli Photography Award 2015; Environmental Journalism Award 2019; Technical Writing Award 2020; Vehicle Testing Review award 2020, runner-up in 2022; Feature Story award winner 2020; inducted into the Street Rodding Hall of Fame in 1994.

Email: jil@ca.inter.net

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jilmcintosh/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JilMcIntosh

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion and encourage all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour for moderation before appearing on the site. We ask you to keep your comments relevant and respectful. We have enabled email notifications—you will now receive an email if you receive a reply to your comment, there is an update to a comment thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information and details on how to adjust your email settings.

Minivans for the whole family

All things automotive: breaking news, reviews and more. Wednesdays and Saturdays.

A welcome email is on its way. If you don't see it, please check your junk folder.

The next issue of Driving.ca's Blind-Spot Monitor will soon be in your inbox.

We encountered an issue signing you up. Please try again

365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4

© 2024 Driving, a division of Postmedia Network Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized distribution, transmission or republication strictly prohibited.

This website uses cookies to personalize your content (including ads), and allows us to analyze our traffic. Read more about cookies here. By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Edit your picks to remove vehicles if you want to add different ones.

Heat Sink Enterprise You can only add up to 5 vehicles to your picks.