Stars of The Love Boat walk along the top of the Great Wall in Beijing at a time when American ... [+] enthusiasm for China was high.

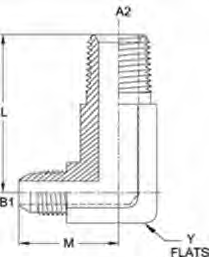

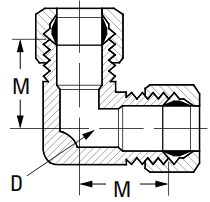

Washington has made it clear that it wants this economy to de-couple from China’s. American business wants the same thing, if not entirely then to a greater degree than in the past. Biden has a national security focus. Business has its own reasons. The efforts, however, are proving to be harder than either the government or business expected. Hose Fittings

Apart from narrow interest groups, Washington, as it should, wants de-coupling to thwart Beijing’s ambitions — to rival this country on economic, diplomatic, and military levels. To lessen the economy’s vulnerability to China, that is American dependence on Chinese imports, and to promote domestic American sources of economic strength, Biden, in contradiction to his campaign promises, has kept in place the Trump tariffs on Chinese imports. The White House has also forbidden the export of advanced semiconductors to China and limited the extent to which Americans can invest in Chinese technology. It has also denied electric vehicle tax credits to any car constructed in China or containing a significant proportion of Chinese parts. Beyond these specifics, Washington wants to limit the vulnerability of the American economy generally should Beijing cut off global supplies of vital products, as it did during the Covid pandemic and even afterwards under its zero-Covid policies.

American business shares some of these concerns but its de-coupling desires spring primarily from other sources. One is a question of cost. For decades after China first opened to the world in the 1970s, a big reason to source in China and build production facilities there was low production costs. But for some time now, Chinese wages have risen more rapidly than elsewhere in Asia and in Latin America. China has ceased to be the low-cost place, an important consideration in any business decision.

Reliability is another issue. Earlier on, China was considered supremely reliable, respectful of contracts and delivering on time. During the Covid pandemic, however, and for a long time afterwards under Beijing’s zero-Covid policies, Chinese producers failed to deliver in designated amounts or on time. What is more, Beijing, during the emergency banned the export of certain products, notably medicinal inputs and surgical masks. If these failures are understandable, American business wants to avoid such problems in the future. Still more recently, Xi Jinping’s obsession with national security has made it more difficult for foreigners to operate in China.

On the surface it appears as though these shared interests are making significant progress on de-coupling. According to the Bureau of the Census, Chinese production in 2017 amounted to fully 22% of all U.S. imports, whereas so far this year, it amounts to only 13%. But these otherwise striking figures disguise some practical difficulties disentangling the U.S. from the Chinese economy.

The problem is that Americans when moving their sourcing to Vietnam or Indonesia or even Mexico are discovering that the best facilities are often Chinese owned. It seems that when Trump first imposed his tariffs, many Chinese firms set up facilities in other countries in order to avoid the levy. According to Beijing’s National Bureau of Statistics, direct Chinese investment in Southeast Asia, for instance, rose from the equivalent of some $7 billion in 2013, before the tariffs went into effect, to some $20 billion in 2022, the most recent period for which data are available. American business looking alternatives to China in these countries, is finding the best options have a link to this Chinese invesstment. The products of these firms, despite the Chinese ownership, show up in the Census Bureau accounting as exports from the host country and not from China. To be sure, ownership matters little in finding economic relief from China’s rules and efforts to thwart U.S. economic advantage, but it does matter a lot if these Vietnamese, Indonesian, or whatever facilities require Chinese-produced inputs, which often is the case.

Metric Hydraulic Fittings American efforts at de-coupling will eventually overcome this impediment. Buying and investment trends as well as attitudinal surveys all show that American business’ desire to diversify away from China has staying power. American businesses will move away from sources that retain a Chinese dependence. At the same time, facilities in these other countries – even those that are Chinese owned – will naturally, as they become more sophisticated, have less dependence on Chinese sources. For the time being, however, the great de-coupling about which so many talk – in Washington and business circles – will run a little less smoothly that either Washington or businesspeople would like.